Photo credit: Keystone Features

When British India was partitioned in 1947, princely states were given the option to join India or Pakistan or remain independent. Jammu & Kashmir initially chose a neutral, independent course. Yet within weeks, the region became part of India. What happened between those decisions and Kashmir’s accession remains a contested and emotional chapter in South Asian history.

BBC correspondent Amir Pirzada visited Kashmir and pieced together key events and eyewitness memories from October 1947 that help explain how the region was absorbed into India.

A Violent Autumn: Tribal Raids, Fear and Flight

In October 1947, 15-year-old Mohammad Sultan Thakur worked at the Mohura hydropower project on the Jhelum. He remembers the sudden arrival of armed bands that locals called “kabalí” — Pashtun raiders who had crossed from what became Pakistan. According to Thakur, the Maharaja’s troops pulled back and the raiders attacked villages and bunkers, opening fire and causing panic.

Residents fled into the nearby forests for days. The memory of those chaotic days — the sound of gunfire, burned houses, and bodies — is still vivid among survivors. Many questions remain about the identity and motives of those who crossed the border: were they rogue raiders, local protectors of Muslim communities, or irregulars backed by Pakistani forces? Historians disagree, and the record is complex.

Outside Fighters and Local Politics

Kashmir’s population was majority Muslim, but its ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh, was Hindu — an arrangement that had produced tensions for decades. From the 1930s onward, Muslim political movements in Kashmir sought greater rights, and the communal violence that accompanied Partition further inflamed the situation.

Some Kashmiri historians, such as Dr. Abdul Ahad, argue that Pashtun irregulars and volunteers from adjoining regions arrived to aid the Muslim population, and to prop up the so-called “Azad” (free) governments declared in areas like Poonch and Muzaffarabad. Others see these incursions as partly a reaction to lawlessness and inter-communal reprisals that were already underway in parts of Jammu.

The attack on the Baramulla area in late October is a painful example. The assault on St. Joseph’s convent and hospital — one of the few Christian institutions in the area — and the killing of nuns and staff became a notorious event. Survivors and witnesses recalled atrocities that later hardened communal divisions.

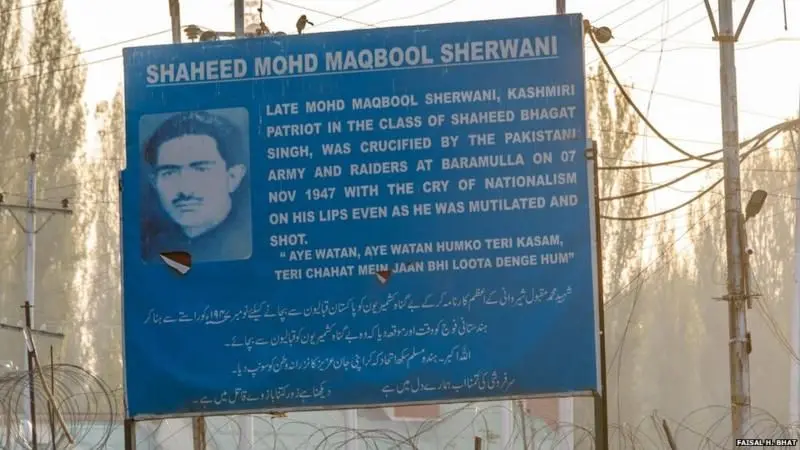

Local Resistance and a Young Hero

Not all Kashmiris supported the invasion. Some resisted. One notable local figure, Mohammad Makbool Sherwani, was just 19 and is remembered for alerting Indian forces to the incursion, an action that helped bring the Indian military to the region on 27 October 1947. Sherwani was later captured and executed; India declared him a martyr.

Sherwani’s story and the mass dislocations of the period (with many fleeing Srinagar’s streets) show the turmoil of those weeks and how local choices were shaped by immediate threats and shifting loyalties.

The Maharaja, Sheikh Abdullah and the Decision to Accede

Maharaja Hari Singh faced a dilemma: he had ruled a culturally diverse state and had tried to maintain autonomy during Partition. But with his forces unable to control the situation and the arrival of armed bands, he sought help.

Behind the scenes, Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah — who had broad support among many Kashmiris — played an important role. Protests erupted in Srinagar with residents demanding protection and siding with Sheikh Abdullah against the Maharaja’s rule. The pressure on Maharaja Hari Singh intensified.

India’s position was that the Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession before fleeing Srinagar — a document that legally brought Jammu & Kashmir into India in late October 1947. Other accounts raise questions about the timing and the specific terms. V.P. Menon, the representative of India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, reached Jammu on 27 October, a day after many key events had occurred.

Critics say some of the promises and conditions that accompanied Kashmir’s accession — including a pledge for a popular plebiscite on its final status — were never implemented fully. That broken promise has been a long-standing grievance for many Kashmiris.

Conflicting Narratives and Lasting Resentment

Historians and Kashmiri voices remain divided. Some, including government-aligned accounts, say accession was necessary and legitimate. Others insist many Kashmiris never wanted to join India and that the decision was made under duress or through political compromise that left local aspirations unfulfilled.

Scholar Andrew Whitehead notes that much of the migration and violence from that era has been forgotten or sidelined in national narratives. Many young Kashmiris now express alienation and distrust: for some, the sense of broken promises persists. Legal students, activists and ordinary citizens voice strong and varied opinions — from those who see India as culpable for failing to honor commitments, to those who believe better integration and outreach could heal old wounds.

A Contested Legacy

The political fallout continued for years. Sheikh Abdullah became Jammu & Kashmir’s first prime minister but his tenure did not last: in 1953, he was arrested under accusations of plotting secession, and his career, like Kashmir’s political history, became a saga of conflict, negotiation and contested authority.

For many Kashmiris today, the memory of 1947 is not simply history — it colors contemporary politics, identity and the aspirations of new generations.

Closing Thought

The story of how Kashmir became part of India is not a single, simple narrative. It is a layered tale of rapid events, local resistance, outside intervention, political bargaining and contested memories. For Kashmiris, Indians and Pakistanis alike, the events of October 1947 remain deeply consequential — and the differing interpretations of those events continue to shape the region’s politics and people’s lives today.

Responses (0 )